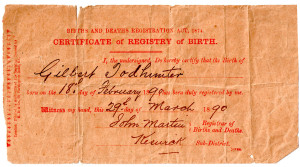

Family Background: Gilbert Todhunter was born in Keswick (above), in the English Lake District, on 18th Feb 1890; his birth certificate is below:

(The name Todhunter is derived from foxhunter, “tod” being the local dialect name for fox. Coincidentally one of the most celebrated foxhunters, John Peel (1776-1854), came from Caldbeck which is just to the north of Keswick).

(The name Todhunter is derived from foxhunter, “tod” being the local dialect name for fox. Coincidentally one of the most celebrated foxhunters, John Peel (1776-1854), came from Caldbeck which is just to the north of Keswick).

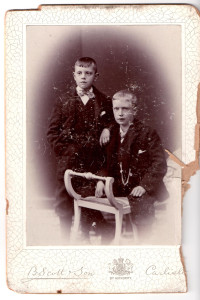

Gilbert’s parents were George (1857-1929) and Margaret (1859-1926) Todhunter. Gilbert grew up with them and his with sisters Florence “Florrie” (1883-1968), Agnes “Aggie” (1886 -1918) and Elizabeth “Lizzie” (1893-1969), and brother John “Jack” (1889-1960). Jack and Gilbert are pictured here (left).

Together with Margaret’s little sister Martha, all lived in a small house (still standing) at 22 Poplar Street, Keswick (right).

Together with Margaret’s little sister Martha, all lived in a small house (still standing) at 22 Poplar Street, Keswick (right).

Character: Gilbert was said in his obituary to be “not at all desirous of obtruding his personality into public notice. Of a quiet and reserved nature, there yet burned within him that spirit of patriotism that finds an outlet in action rather than in words”, as was soon to become evident.

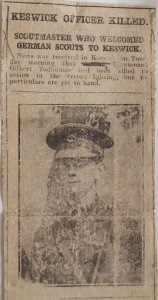

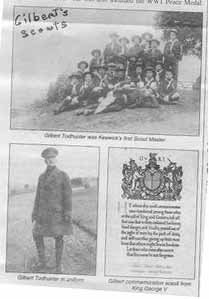

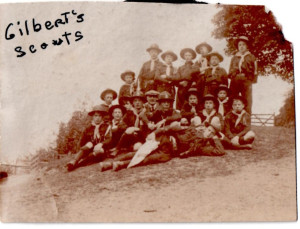

School & Scouts: Gilbert attended Brigham School (right) on Penrith Road in Keswick, and with friends set up the first Keswick Scout Troop (below) in 1909, shortly after Baden Powell had formed the movement in 1907. Gilbert first became Patrol Leader of the troop before being elected its first Scoutmaster, as indicated by the plume on his hat badge (right).

Gilbert first became Patrol Leader of the troop before being elected its first Scoutmaster, as indicated by the plume on his hat badge (right).

In this capacity, on 11th July 1909, Gilbert welcomed to Keswick a party of 20 Wandervogel from Germany (an equivalent of English Scouts but a little older), and with his own scouts led the combined troop in procession through Keswick.

(Also, according to one source, Gilbert even found time to be the secretary for the local YMCA).

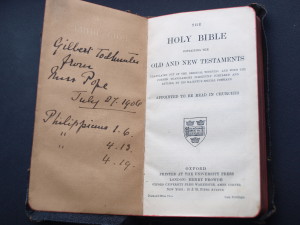

Religion: It is not clear now whether Gilbert was a member of any particular church, although his father George was a Wesleyan Methodist, and we are told in his obituary that Gilbert “strove by example to carry out not only the Scout Law, but the Christian life which embodies it”. In 1906, at the age of 16, he was given a Holy Bible (below) by a Miss Pope, possibly someone at church.

When he subsequently sailed for Canada he put down his religion as Wesleyan, although his passage was subsidised by the Salvation Army – yet not long after arriving there he was confirmed & later married in the Anglican church. We do not know if he formally attended church in Keswick; if he did, there was at the time a Wesleyan chapel and Sunday school on Southey Street (his father supported a Wesleyan group at the Threlkeld Mission Room nearby).

There are two Anglican churches in Keswick too; the nearest to his home being St John’s, but St Kentigern’s church at Crosthwaite, where his mother used to live, was also not far away. His sister Agnes and later his widow were to become active in the Salvation Army, but there is no record of Gilbert’s interest in it although as stated above his later passage to Canada was subsidised by them.

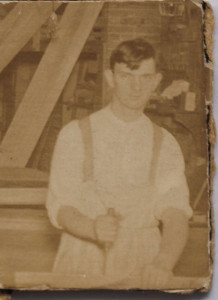

Training & Employment: On leaving school, Gilbert worked first for a Mr Dumble,  a picture framer in Borrowdale Road Keswick. Dumble regarded Gilbert as “a thoroughly reliable young man”. Perhaps this awoke an interest in a career in working with wood, because after two years with Mr Dumble, Gilbert became apprenticed as a carpenter to a Mr Charles Clark of 67/69 Main Street Keswick, Joiner, cabinet maker & furnisher.

a picture framer in Borrowdale Road Keswick. Dumble regarded Gilbert as “a thoroughly reliable young man”. Perhaps this awoke an interest in a career in working with wood, because after two years with Mr Dumble, Gilbert became apprenticed as a carpenter to a Mr Charles Clark of 67/69 Main Street Keswick, Joiner, cabinet maker & furnisher.

The photo to the right shows Gilbert at work. Although later in Canada he was to describe himself as a “carpenter/ builder”, he possessed a 19-piece set of woodcarving tools (below).

These would indicate an earlier interest in the finer aspects of woodwork too, developed no doubt whilst working for Mr Clark, and which he would have used later to make a wooden box (see below) in the style, almost, of a piece of portable furniture.

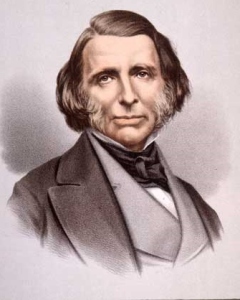

This raises the question of how he was trained in woodcarving, and how far this may have laid outside the scope of a working carpentry apprenticeship. At this time in Keswick, a school of “industrial arts” had been founded (in 1884) by Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley (1851-1920), vicar of St Kentigern’s church, and his wife Edith.

(Rawnsley was , one of the founders of the National Trust, a family friend of Beatrix Potter (1866-1943), and the acting chaplain of the local TA unit). The school offered classes in drawing, design, woodcarving, metalwork and the spinning of flax and embroidery, in accordance with the philosophy of the Arts & Crafts movement. I

(Rawnsley was , one of the founders of the National Trust, a family friend of Beatrix Potter (1866-1943), and the acting chaplain of the local TA unit). The school offered classes in drawing, design, woodcarving, metalwork and the spinning of flax and embroidery, in accordance with the philosophy of the Arts & Crafts movement. I n this, Rawnsley (right) was influenced by his friend and fellow Lakeland resident, John Ruskin (1819-1900).

n this, Rawnsley (right) was influenced by his friend and fellow Lakeland resident, John Ruskin (1819-1900).

The classes were aimed at working men & lads, especially those such as Gilbert whose occupations were to a large extent seasonal. The school (the Keswick School of Industrial Arts, or KSIA) also produced items for sale, eventually focusing primarily on metalwork products, and “KSIA”-branded items now command premium prices on the antiques market.

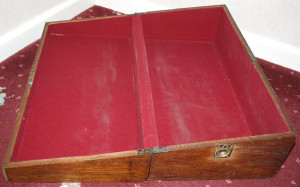

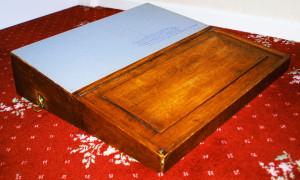

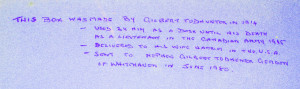

Whether or not Gilbert really did attend the KSIA, he did carry out woodcarving and in 1914 he did create the wooden box – designed to carry personal items and to double as a writing desk – which he was to take on his travels across the Atlantic and back (as indicated by his nephew’s handwritten note on the bottom). Unlike much arts & crafts work however, it is of necessity rather plain – but it would be nice to think he was involved with KSIA since it was active in Keswick during his time.

The wooden box; details below

As befits its purpose, the box exhibits a rather plain style of Arts & Crafts work rather that the more ornate style favoured by some A&C projects. It still however demonstrates a considerable degree of woodworking skill and metalwork too, evidenced by the inset handles and the Fleur-de-Lys (Scouts’ emblem) design of the lock plate.

Territorial Army: In 1905 at age of 15, he joined the Territorial Army (Army Reserve) Unit of the Border Regiment .  The red centre of his cap badge (right) denotes the TA, and the Latin motto “Tre Juncta in Uno” on his tunic buttons means three joined in one, a reference to the union of England & Wales, Scotland and (Northern) Ireland. Gilbert’s leadership qualities enabled him to reach the rank of Captain, and he may have been instrumental in establishing a new TA troop at the Drill Hall in Southey Street Keswick in 1910. The acting chaplain at the time was Canon Rawnsley (above).

The red centre of his cap badge (right) denotes the TA, and the Latin motto “Tre Juncta in Uno” on his tunic buttons means three joined in one, a reference to the union of England & Wales, Scotland and (Northern) Ireland. Gilbert’s leadership qualities enabled him to reach the rank of Captain, and he may have been instrumental in establishing a new TA troop at the Drill Hall in Southey Street Keswick in 1910. The acting chaplain at the time was Canon Rawnsley (above).

Gilbert trained with the TA as a signalling officer, the signalling function providing communications by means of visual signalling, postal and despatch, telegraph and wireless.

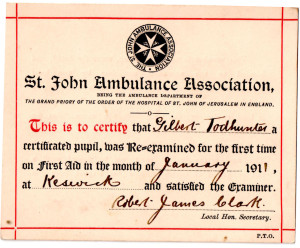

Whether as a consequence of his scouting, his employment or his membership of the TA, in 1911 Gilbert was awarded a 1st Aid Certificate from St John’s Ambulance (right).

Whether as a consequence of his scouting, his employment or his membership of the TA, in 1911 Gilbert was awarded a 1st Aid Certificate from St John’s Ambulance (right).

Romance & Emigration: By April 1911, Gilbert’s sister Lizzie had moved to Hale near Altrincham in Cheshire to work as a domestic servant for a couple from Egremont in Cumberland (now Cumbria), a Mr & Mrs Moffatt. At about this time a young lady named Harriet Bebbington (left) from Crewe had also been living and working as a domestic servant in the area. They apparently met there and formed a lasting friendship, and Lizzie introduced Harriet to her family.

Romance & Emigration: By April 1911, Gilbert’s sister Lizzie had moved to Hale near Altrincham in Cheshire to work as a domestic servant for a couple from Egremont in Cumberland (now Cumbria), a Mr & Mrs Moffatt. At about this time a young lady named Harriet Bebbington (left) from Crewe had also been living and working as a domestic servant in the area. They apparently met there and formed a lasting friendship, and Lizzie introduced Harriet to her family.

Harriet clearly took to both Aggie (by then working for the Salvation Army in Holywell, North Wales) and Gilbert, such that the three of them decided together to emigrate to Canada. At the time, the Salvation Army was acting as an agency for Canadian immigration and offered assisted passages to SA members and non-members alike, and this would have attracted all three to the idea of living in the New World.

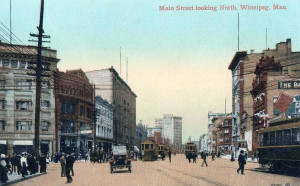

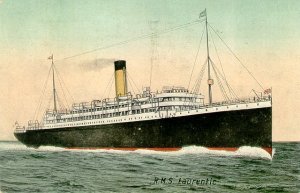

Gilbert embarked on the SS Laurentic (right) out of Liverpool, arriving in Quebec on the 13th May 1911, and headed for Winnipeg, Manitoba; Agnes and Harriet joined him the following May. After arrival at Quebec, Aggie and Harriet both rendezvoused with Gilbert in Winnipeg. Aggie then moved around Central Canada (Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan), spreading the Gospel there. Gilbert & Harriet settled together in Winnipeg, Manitoba (see old photo of Winnipeg – and city pin badges).

Gilbert embarked on the SS Laurentic (right) out of Liverpool, arriving in Quebec on the 13th May 1911, and headed for Winnipeg, Manitoba; Agnes and Harriet joined him the following May. After arrival at Quebec, Aggie and Harriet both rendezvoused with Gilbert in Winnipeg. Aggie then moved around Central Canada (Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan), spreading the Gospel there. Gilbert & Harriet settled together in Winnipeg, Manitoba (see old photo of Winnipeg – and city pin badges).

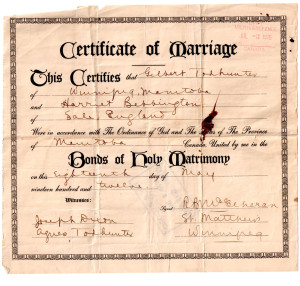

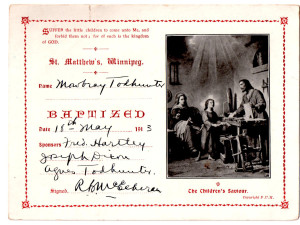

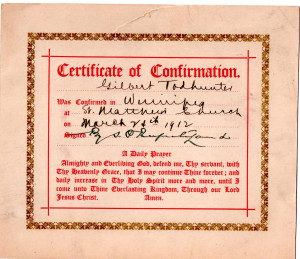

Life in Canada: Gilbert was confirmed (right) in St Matthew’s Anglican church on 14th March 1912 , prior to their marriage (below) at the same church on 18th May that year, once Harriet had arrived.

Life in Canada: Gilbert was confirmed (right) in St Matthew’s Anglican church on 14th March 1912 , prior to their marriage (below) at the same church on 18th May that year, once Harriet had arrived.

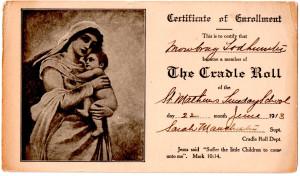

The pair set up their marital home at 550 Polson Avenue Winnipeg (above c. 2018), and after a year their first child was born, a boy named Mowbray after Harriet’s employer in Sale. Mowbray was christened at St Matthews’ on 18th May 1913, and enrolled into the church’s Cradle Roll on 22nd June.

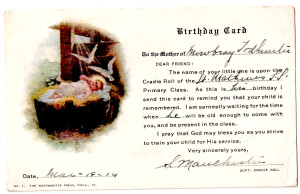

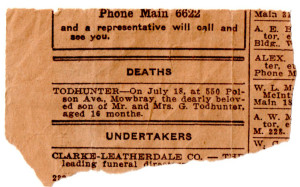

By this time Gilbert’s father George, having been inspired by the example shown by his son & daughter, had also sailed on SS Empress of Britain (below) in May 1913, to set himself up near Gilbert in Winnipeg, to work for the Canadian Pacific Railroad as a telegrapher. In March 1914 the Cradle Roll sent Mowbray his first birthday card, but sadly on 18th July he died aged just 16 months.

By this time Gilbert’s father George, having been inspired by the example shown by his son & daughter, had also sailed on SS Empress of Britain (below) in May 1913, to set himself up near Gilbert in Winnipeg, to work for the Canadian Pacific Railroad as a telegrapher. In March 1914 the Cradle Roll sent Mowbray his first birthday card, but sadly on 18th July he died aged just 16 months.

Meanwhile Gilbert had resumed his occupation as a carpenter and had joined the Winnipeg branch of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners. He also became a member of the Ancient Order of Foresters, a Freemason-type organisation (below); the army cadets as an instructor; and the Canadian Militia (still as a signalling officer with the rank of Captain), the Canadian equivalent of the TA. Gilbert & Harriet kept in touch with Aggie, some 250 miles away, as well as his father nearby. In early 1914, Harriet became pregnant for the second time.

Meanwhile Gilbert had resumed his occupation as a carpenter and had joined the Winnipeg branch of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners. He also became a member of the Ancient Order of Foresters, a Freemason-type organisation (below); the army cadets as an instructor; and the Canadian Militia (still as a signalling officer with the rank of Captain), the Canadian equivalent of the TA. Gilbert & Harriet kept in touch with Aggie, some 250 miles away, as well as his father nearby. In early 1914, Harriet became pregnant for the second time.

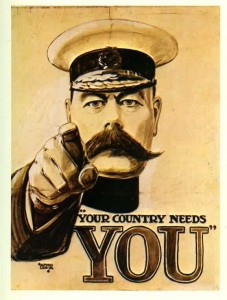

Gilbert at war: On 4th August 1914 Britain declared war against Germany and World War 1 commenced; the British Expeditionary Force was in France from early August. The famous poster featuring Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War (right), was used to encourage recruits to the British & Empire war effort.

Canada supported Britain as a member of the Empire under King George V (left), and a souvenir edition of the Canadian News was published to record Britain’s acknowledgement of the Canadians’ role.

Canada supported Britain as a member of the Empire under King George V (left), and a souvenir edition of the Canadian News was published to record Britain’s acknowledgement of the Canadians’ role.

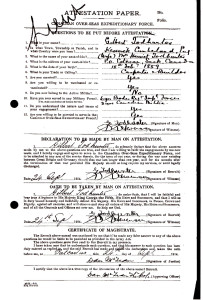

Gilbert completed an Attestation Paper (right), indicating his readiness to serve at war, (note – he incorrectly stated his year of birth on this form, thereby overstating his age by one year. He also stated his address as Aggie’s Estevan address, expecting that he and Harriet would both be leaving Winnipeg, for places unknown).

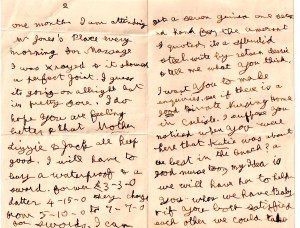

Gilbert’s application was for transfer to the regular Canadian Army as a signaller in the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force, which was confirmed on 24th September.  Gilbert had been said to be “an expert signaller, always devoted to the study of military tactics”, and enlisted at Camp Valcartier Quebec in the 10th Infantry Battalion, 106th Winnipeg Light Infantry. (see cap & collar badges left).

Gilbert had been said to be “an expert signaller, always devoted to the study of military tactics”, and enlisted at Camp Valcartier Quebec in the 10th Infantry Battalion, 106th Winnipeg Light Infantry. (see cap & collar badges left).

Pictured in uniform (right), Gilbert was able to keep his commission, albeit at the lower rank of 2nd Lieutenant – again a signalling officer.

Pictured in uniform (right), Gilbert was able to keep his commission, albeit at the lower rank of 2nd Lieutenant – again a signalling officer.

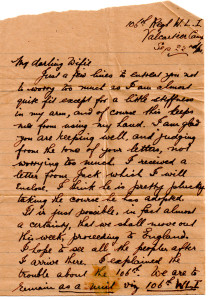

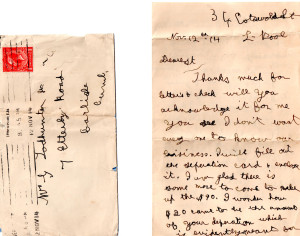

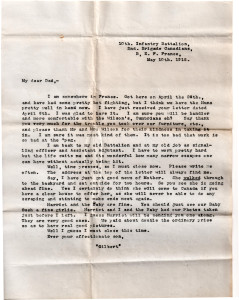

He commenced training while still in Canada, during which he broke his arm, so he had to get a comrade to write a letter home to Harriet which he dictated (below):

In this letter he states that he expects to be shipped to England shortly for training, and suggests that Harriet might move to England too. In the meantime Gilbert’s brother Jack had joined the British Army as a Sapper in the Royal Engineers.

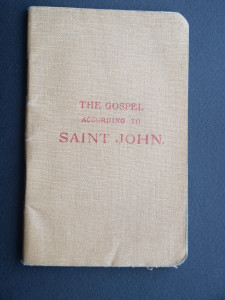

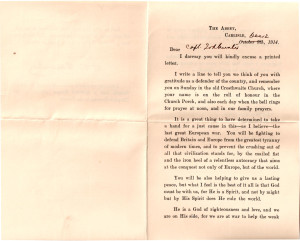

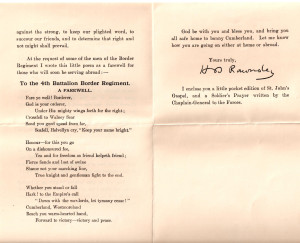

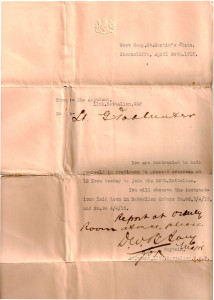

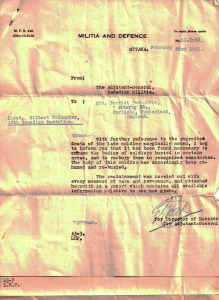

On 9th October Canon Rawnsley (by now Dean of Carlisle Cathedral, and Chaplain to the King) sent a standard, pre-printed letter (below) to all Border Regiment officers going to war (his staff erroneously assumed that Gilbert was still in the regiment, as a Captain) and enclosing a pocket Gospel according to St John:

Gilbert transferred to England with the Canadian forces (early photo of signalling team right; Gilbert appears standing 5th from left ).

Gilbert transferred to England with the Canadian forces (early photo of signalling team right; Gilbert appears standing 5th from left ).  Most of these landed at Plymouth on 15th October, although there are indications that Gilbert sailed into Liverpool.

Most of these landed at Plymouth on 15th October, although there are indications that Gilbert sailed into Liverpool.

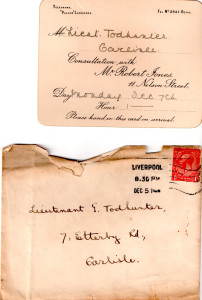

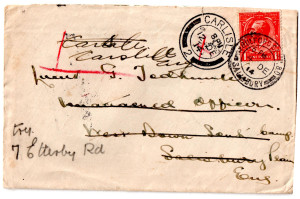

By 12th November Harriet had arrived too, and went to stay with his mother and Lizzie who by then had moved to 7 Etterby Road Carlisle. They brought all their belongings back too, having relinquished their accommodation in Winnipeg, retaining Aggie’s Estevan address as their Canadian forwarding address.

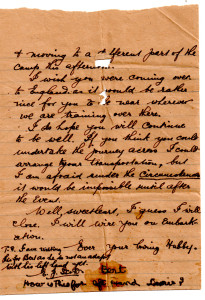

Gilbert wrote to Harriet from Liverpool on November 12th (below), in his own hand now, although still suffering some discomfort from his injured arm. The letter is scrawled but still legible, and in it he mentioned the sword he is about to buy from a Liverpool maker (up to 7 guineas for a new one or £4.5s for a 2nd hand one).

The sword he bought (below) was engraved with his own name as well as the makers’, and the hilt contained the emblem of King George V. It came with a leather scabbard for operational use and a silver one for ceremonial duties.

In his letter Gilbert also pointed out the need to find a good nursing home for the new baby’s birth. (NB: this is the last letter that we have of Gilbert to Harriet (other than a postcard), and none from Harriet to Gilbert. The remaining documents are therefore either formal or at least fairly unemotional; this does not mean that their private letters, if they remain wherever they are, were similarly formal & unemotional).

Their second child Eileen was born in Carlisle on 20th December 1914. Meanwhile Gilbert had been in Liverpool to see a leading specialist in bone injuries, Robert Jones, on 7th December about his broken arm (see appointment card left).

Their second child Eileen was born in Carlisle on 20th December 1914. Meanwhile Gilbert had been in Liverpool to see a leading specialist in bone injuries, Robert Jones, on 7th December about his broken arm (see appointment card left).

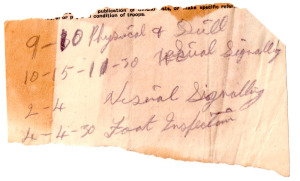

Gilbert’s training in England started under canvas on Salisbury Plain, primarily focused on his already-established signalling and leadership skills,  and while there he underwent a field officers’ course for a major’s certificate.

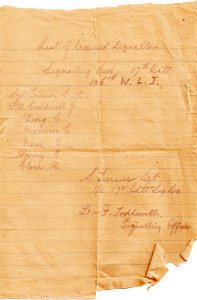

and while there he underwent a field officers’ course for a major’s certificate.  He made notes (including a list of signallers in his team) on whatever scraps of paper came to hand:

He made notes (including a list of signallers in his team) on whatever scraps of paper came to hand:

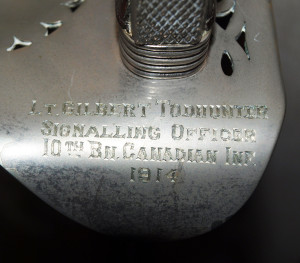

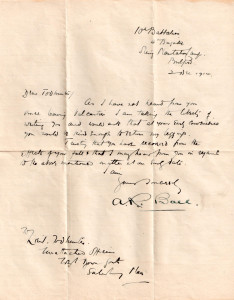

In December he received in Carlisle a letter (which from the envelope had been forwarded via Salisbury Plain) from an A.R.Ball, asking for the return of some leggings he had borrowed when he was injured.

It is thought that this A.R.Ball was Lieut. Albert Ransom Ball from Winnipeg, like Gilbert in the Winnipeg Light Infantry (Ball died of wounds in Boulogne Hospital on 30 April 1915).

It is thought that this A.R.Ball was Lieut. Albert Ransom Ball from Winnipeg, like Gilbert in the Winnipeg Light Infantry (Ball died of wounds in Boulogne Hospital on 30 April 1915).

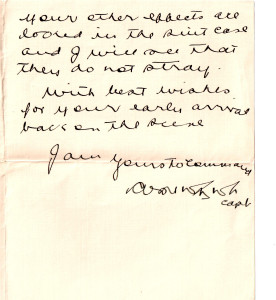

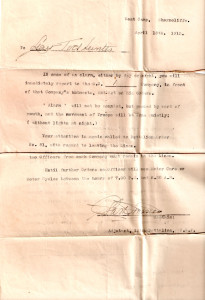

Also in December 1914, Gilbert was sent a letter (below) from a captain at Camp Valcartier, discussing some financial & administrative matters including the despatch of Gilbert’s belongings and promising to take care of them.

From around the time he enlisted, Gilbert carried a tiny compass,  a sealing-wax stamp of the letter ‘T’, a small butterfly brooch,

a sealing-wax stamp of the letter ‘T’, a small butterfly brooch,  and two thin leather straps, one with two coins attached (a Mexican 1c coin and a commemorative coin for Queen Victoria ).

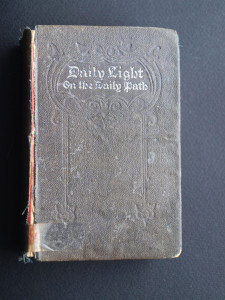

and two thin leather straps, one with two coins attached (a Mexican 1c coin and a commemorative coin for Queen Victoria ). He also carried his childhood pocket bible, Rawnsley’s gospel, a “Daily Light” book of biblical quotations, a YMCA book of camp songs, and a diary.

He also carried his childhood pocket bible, Rawnsley’s gospel, a “Daily Light” book of biblical quotations, a YMCA book of camp songs, and a diary.

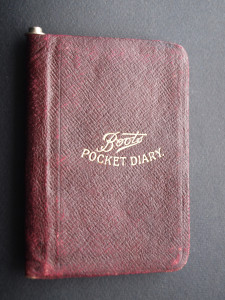

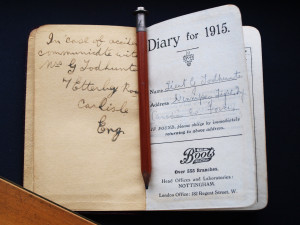

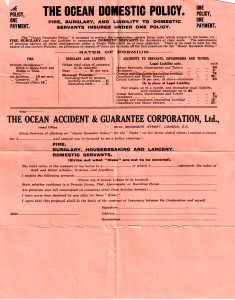

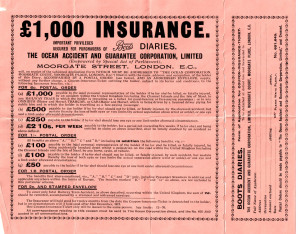

Gilbert’s 1915 Diary: While in England Gilbert had bought a 1915 pocket diary from Boots, the price of which included an Accident Insurance policy for £1,000 from Ocean Insurance. In this he recorded his personal details as well as his experiences on a daily basis between New Year 1915 and his last entry on 15th May.

The diary takes Gilbert’s story forward from this point (see ‘Gilbert’s Diary’ page for images of the actual diary pages) . This shows that Gilbert and Harriet kept in touch with each other throughout, as much as they could, with Harriet sometimes even sending food & other items, although we don’t have any of their personal letters. The following paragraphs summarise what Gilbert’s diary tells us.

– Gilbert spent New Year 1915 at home (right) in Carlisle with Harriet and the rest of the family, and of course his new baby, Eileen.

– Gilbert spent New Year 1915 at home (right) in Carlisle with Harriet and the rest of the family, and of course his new baby, Eileen.

– On 12th January, after receiving orders to report to his senior officer, he packed up and travelled to Salisbury Plain for medical examination and training.

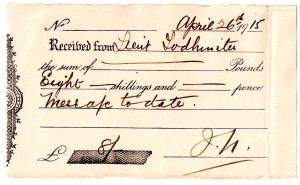

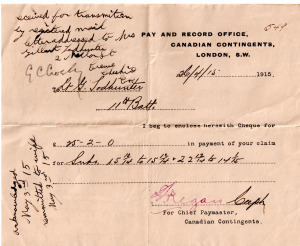

– He spent the rest of January & most of February rejoining the Canadian troops; undertaking guard duties & inspections; participating in training sessions, marches & parades; and in social and administrative activities.  Paperwork he left behind included a Remittance Advice for a claim for “subs” (the amount to be forwarded to Harriet), and a mess bill receipt.

Paperwork he left behind included a Remittance Advice for a claim for “subs” (the amount to be forwarded to Harriet), and a mess bill receipt.

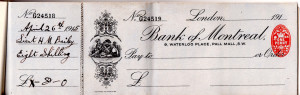

– He referred on 14th February to receiving a Bank of Montreal pay cheque (he had a cheque book for the Bank of Montreal, London branch).

– He referred on 14th February to receiving a Bank of Montreal pay cheque (he had a cheque book for the Bank of Montreal, London branch).

– He went back to Carlisle from 20th-23rd February, to see his mother who was sick, before returning to Salisbury Plain to resume training.

– In early March the battle of Ypres on the Western Front was under way. Meanwhile Gilbert’s training continued, but on 10th March he was feeling quite sick in camp (no suggestion that this was in apprehension of the terrors to come).

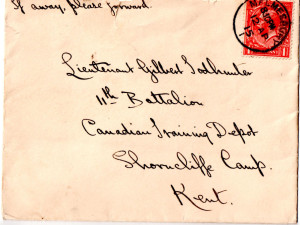

– He moved on 26th March to the staging post at Shorncliffe Camp Folkestone to await orders to travel to France. He was clearly pleased about having huts now instead of the tents on Salisbury Plain. He took the opportunity to go for walks and to explore the area.

(Shorncliffe was established as a British Army Camp as early as 1794, and it still in use in 2015, now known as Shorncliffe Garrison. It occupies a large flat area of land above the cliffs to the west of Folkestone, close to Cheriton. Shorncliffe is featured in the “Step Short” website http://www.stepshort.co.uk which also links to this article in Saga Magazine of November 2013:

Folkestone is a cliff-top town so the troops would have to have marched down a steep hill towards the harbour at the bottom. The order “Step Short” was given to instruct the soldiers to adjust their marching pace for the downhill slope).

– He went back home from 31st March to 6th April, to celebrate Easter with the family and to attend Lizzie’s wedding, where he was her male witness. He records that he took Harriet to the theatre, and ordered some new boots from the Co-op.

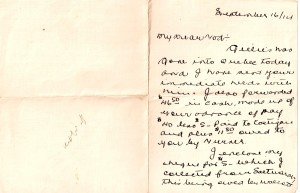

– On 8th April, Gilbert was sent a letter from his father George, who had arranged for Gilbert & Harriet’s furniture to be stored with a Mr & Mrs Wilson. It appears that George must also have moved in with them.

– On 9th April Harriet came to Folkestone with baby Eileen to see him; that would be the last time they would spend together. She then returned to stay with her parents at 7 Mellor Road Crewe, Cheshire. Meanwhile his new boots arrived on the 10th, along with a ring from home.

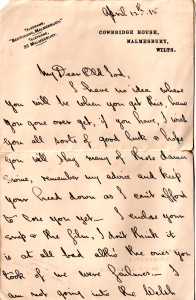

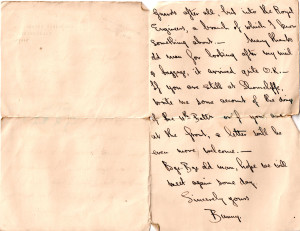

– On or around the 15th April, Gilbert received a letter from a friend “Bunny” in Malmesbury, who was about to join the Royal Engineers, wishing him well. (“Bunny” was William Cruden de Bertodanoa, a very well-connected civil engineer with a wealthy & powerful Spanish background. The family owned a substantial house in Malmesbury as well as a London town house. Before the war he was in the Territorial Army so possibly he met and formed a friendship with Gilbert at a TA training camp).

– On the 18th April, Gilbert records in his diary that he was “at home”; we cannot be sure which “home” he meant here. Tension at Shorncliffe would have been building through April; practice intensified, and Gilbert received a note from his Adjutant about alarms. This would have arrived in an OHMS (On His Majesty’s Service) envelope like the one below. This was addressed to Gilbert at Cheriton, close to Shorncliffe on the outskirts of Fokestone. Maybe he was billeted here, or maybe this address had been requisitioned as a mailing address.

– On the 18th April, Gilbert records in his diary that he was “at home”; we cannot be sure which “home” he meant here. Tension at Shorncliffe would have been building through April; practice intensified, and Gilbert received a note from his Adjutant about alarms. This would have arrived in an OHMS (On His Majesty’s Service) envelope like the one below. This was addressed to Gilbert at Cheriton, close to Shorncliffe on the outskirts of Fokestone. Maybe he was billeted here, or maybe this address had been requisitioned as a mailing address.

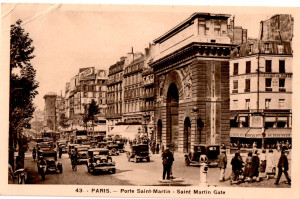

– On 23rd April, Gilbert received a London postcard (below) from his brother Jack, who by then had already arrived in France, having been unable to meet up at the weekend as Gilbert had suggested.(It appears that Jack had also visited Paris because Gilbert had in his collection a blank postcard from there – below right).

– On 24th April, Gilbert received another note (right) from the Adjutant instructing troops to hold in readiness.

– On 24th April, Gilbert received another note (right) from the Adjutant instructing troops to hold in readiness.

– Then Gilbert received a miniature photo of Harriet, just in time for he and his troop (below) to sail for France, on 26th April.

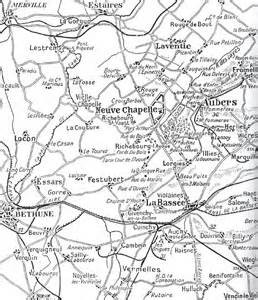

– They arrived (below) at Havermille in the war zone of the Western Front, on 27th April, and came under shellfire from as early as the 28th (it is not clear exactly where Havermille is, but subsequent events lead us to assume that this was in the area of Flanders bounded roughly by Bethune, Bailleul, Armentiers and Lille, where most of the action was taking place at that time).

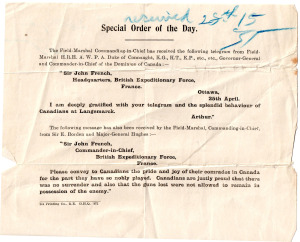

– Also on that day, a note was received from Sir John French, the Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces, in appreciation of the recent efforts of Canadian troops at Langemark near Ypres.

– Also on that day, a note was received from Sir John French, the Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces, in appreciation of the recent efforts of Canadian troops at Langemark near Ypres.

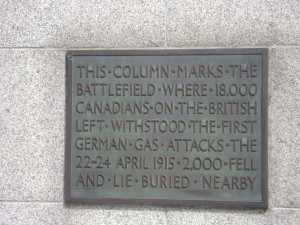

(In truth this battle was far from joyful. This was the first time that Allied troops, Canadians included, had faced a German gas attack, leading to the loss of 2,000 men.  They are commemorated in a Garden of Remembrance at Vancouver Corner, between Langemark & Ypres, where stands “the Brooding Soldier” (below), an 11 m-high statue of a Canadian Soldier with his head bowed and weapon upturned as a symbol of respect for the dead. He stands in a garden planted with junipers and other shrubs designed to reflect the creeping green gas clouds which so devastated the troops who stood in its way).

They are commemorated in a Garden of Remembrance at Vancouver Corner, between Langemark & Ypres, where stands “the Brooding Soldier” (below), an 11 m-high statue of a Canadian Soldier with his head bowed and weapon upturned as a symbol of respect for the dead. He stands in a garden planted with junipers and other shrubs designed to reflect the creeping green gas clouds which so devastated the troops who stood in its way).

– From 29th April, they were in the trenches (left) and things were getting increasingly hectic,  which might explain why his diary entries became rather more difficult to decipher, presumably due to increased tension and reduced facilities in the field.

which might explain why his diary entries became rather more difficult to decipher, presumably due to increased tension and reduced facilities in the field.

– On May 1st, Gilbert came under shellfire; “strung wires meanwhile”, as he put it. After receiving a photograph from Harriet (and some sandwiches), Gilbert wrote back to her from “somewhere in France”.

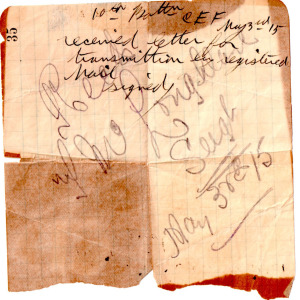

– On 3rd May, Gilbert received a cheque from Pay & Records office – Sub. Allowance £25-2-0 – and a letter – source unknown (he kept a note of its receipt).

– On 3rd May, Gilbert received a cheque from Pay & Records office – Sub. Allowance £25-2-0 – and a letter – source unknown (he kept a note of its receipt).

– On 5th May they left the trenches, still under heavy shellfire, and walked 10 miles – this would have been to give some respite while they recovered from the stress of the front line. Practise and administrative work had to continue, however.

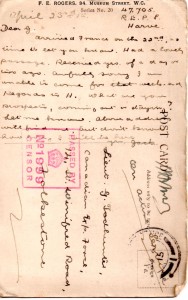

– On 10th May, Gilbert sent a typed letter (below) to his father George from ”somewhere in France”, describing some “pretty hot fighting”, but that he thought they “had the Hun pretty well in hand”. He adds, showing his British stiff upper lip, “It’s wonderful how many narrow escapes one can have without actually being hit”.

This letter implies that George had been separated at least temporarily from his wife Margaret, because it informs George that she was on the road to recovery from her illness, and he thought that she would go to Canada a subject to certain conditions (like a house to live in and no “scraping and stinting to make ends meet”). Thus Gilbert was trying to reassure George both that he was safe and well in France, and that his mother was likely to join George in Canada – neither turned out to be true.

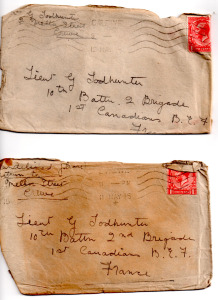

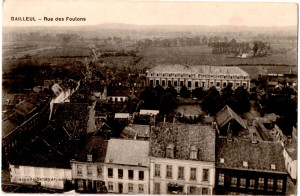

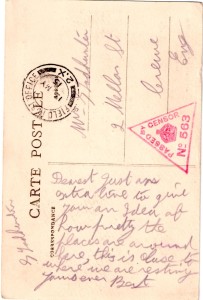

– On 11th May Gilbert received 2 letters from Harriet in Crewe (envelopes only remain), and on 13th May he sent her a postcard of the nearby village of Bailleul, close to where his troop was resting.

He describes Bailleul as a “pretty place”, but during Gilbert’s visit it was a pretty hectic place too. It had been occupied by the Canadian Army for wartime use as a railhead, air depot and casualty clearing centre. The large building in the middle distance of the photo was actually a boys’ school requisitioned in the war as a hospital.

He describes Bailleul as a “pretty place”, but during Gilbert’s visit it was a pretty hectic place too. It had been occupied by the Canadian Army for wartime use as a railhead, air depot and casualty clearing centre. The large building in the middle distance of the photo was actually a boys’ school requisitioned in the war as a hospital.

Today (2015), Bailleul remains an attractive little town, with a large cobbled square surrounded by traditional buildings and dominated by a rather grand Town Hall (left).

Today (2015), Bailleul remains an attractive little town, with a large cobbled square surrounded by traditional buildings and dominated by a rather grand Town Hall (left).

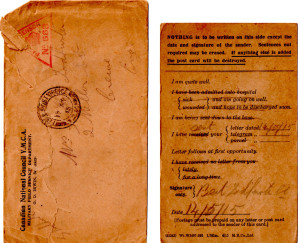

– On 14th May Gilbert sent a Field Service Postcard (right) to Harriet in Crewe, saying he is “quite well”, having received her letter and promising to reply soon.

This would probably have been the last she ever heard from him.

– His last diary entry was on 15th May – presumably the pressures of war prevented him from adding any more. It appears that Gilbert was already living dangerously, having had some narrow escapes, even before his troop went into action at Festubert in France on May 17th, 1915.

On the 16th he was sent a letter (left) from a W.S.Cooper, a friend & fellow officer, in an Army Form envelope. This may have been the last letter he ever received.

On the 16th he was sent a letter (left) from a W.S.Cooper, a friend & fellow officer, in an Army Form envelope. This may have been the last letter he ever received.

The Battle of Festubert: Festubert is now, and no doubt was at the time, a quiet sleepy village surrounded by fields and orchards. (See photos of the village, taken in 2015, and a nearby country road). It lies in the area bounded roughly by Bethune, Bailleul, Armentiers and Lille, in northern France.

The Battle of Festubert: Festubert is now, and no doubt was at the time, a quiet sleepy village surrounded by fields and orchards. (See photos of the village, taken in 2015, and a nearby country road). It lies in the area bounded roughly by Bethune, Bailleul, Armentiers and Lille, in northern France.

In 1915 it was right on the Western Front, which ran roughly north-south from near Ostend on the channel, past Ypres & Lille to Arras & beyond. The allies’ aim in 1914/15 was to push the enemy back to the east along this front, although limited resources meant that action could not take place simultaneously along the whole front, so numerous battles took place at different points at different times – many in or near the villages around Festubert, such as Neuve Chapelle and Aubers.

In 1915 it was right on the Western Front, which ran roughly north-south from near Ostend on the channel, past Ypres & Lille to Arras & beyond. The allies’ aim in 1914/15 was to push the enemy back to the east along this front, although limited resources meant that action could not take place simultaneously along the whole front, so numerous battles took place at different points at different times – many in or near the villages around Festubert, such as Neuve Chapelle and Aubers.

Although Gilbert made relatively little of it in his correspondence and his diary, this area was deep in the thick of heavy fighting. It consists of flat, fertile but easily-flooded farmland offering little cover, and with wide drainage ditches difficult to cross. It got very muddy after heavy rain – and in spring 1915, it rained heavily, rendering Flanders’ fields a sea of mud.

A few miles to the north, the battle at Langemark (just north of Ypres) had concluded with the loss of 2,000 Canadian troops, on 24th April – the very day when Gilbert and his troop received their orders to stand by for sailing for France, arriving on the 27th.

The next allied offensive, the battle of Aubers (just west of Lille), had been scheduled for 8th May; Gilbert’s battalion was heavily involved in the preparation, during which they had come under shellfire in the trenches from as early as the 28th. Enemy shelling continued until 5th May, during which period Gilbert was laying communications lines and captured some enemy spies. From the 5th they moved to rest near Bailleul, some 20 miles from the lines; Gilbert made no more diary entries about the fighting.

The onset of the battle of Aubers was delayed a day to the 9th, and by the early hours of the 10th it was over; judged subsequently as an unmitigated disaster. The allies had attempted to push too far, too fast over too wide a front with too little intelligence and too few resources, and with inadequate equipment and supplies. The British Army alone suffered 11,000 casualties that day, and the front was pushed back west again.

The battle of Festubert was regarded as the second phase of the battle of Aubers, Festubert being a short distance to the west of Aubers. This time the tactics were to bombard the German lines with heavy artillery for a prolonged period, softening up the enemy before making much more concentrated infantry attacks on their trenches. Previous weaknesses in intelligence, resources, equipment and supplies were addressed, and the allied trenches were better organised for movement of reinforcements and casualties.

The battle of Festubert was regarded as the second phase of the battle of Aubers, Festubert being a short distance to the west of Aubers. This time the tactics were to bombard the German lines with heavy artillery for a prolonged period, softening up the enemy before making much more concentrated infantry attacks on their trenches. Previous weaknesses in intelligence, resources, equipment and supplies were addressed, and the allied trenches were better organised for movement of reinforcements and casualties.

The artillery bombardment commenced on 13th May, while Gilbert and his comrades were still resting near Bailleul. By the night of the 15th – the date of Gilbert’s last diary entry – many of the allied infantry divisions were in place ready for attack on the 16th. When they did attack however, they found that some of the British heavy guns were by now getting worn and inaccurate, and some were based upon soft ground, so the infantry found themselves shelled at times from both sides.

The Canadian troops, Gilbert and his men included, went into action on the 17th. Fighting over unfamiliar territory, they found that their maps contained unfamiliar symbols too, and were printed upside down in relation to normal maps which had north to the top. In a subsequent newspaper article, the 10th Battalion’s CO commented that he had had to have his own, more accurate, maps drawn up.

The allied battle plans proved complex and difficult to execute, and uncertainty and disorientation often prevailed amongst the allied troops, but despite these setbacks, they pushed on, making several tactical advances across the muddy fields towards the Aubers ridge. Fighting continued through the 18th & 19th, some divisions relieving others, then on the 20th renewed artillery bombardments took place from 4.00 am in preparation for more infantry attacks from 7.30 am – the aim being to gain 600-1,000 yards’ new ground towards a small orchard to the east of Festubert.

Gilbert’s 10th battalion had moved during the night of the 19th into trenches previously occupied by the Germans, which they found to be in poor condition, containing many unburied corpses and unattended wounded men. (Some weeks after the end of the battle, these same trenches were visited by soldiers from the Royal Artillery, who found the German corpses still there, but by then there were some dead bodies of Canadian troops too).

The Canadians were commanded by Brigadier-General Currie, who protested vehemently when the order to attack was received, requesting a day’s postponement to be better prepared in the prevailing conditions, but his objections were overruled.

The C.O. of the 10th Battalion, Lieut. Col. Percy A. Guthrie, led the assault on K5, which he later described as “a fort in the German line constructed of concrete and sandbags in which numerous machine guns were mounted so as to sweep the ground in every direction”. This did not go well. They had poor supporting fire from the allied artillery and the planned blasting of K5 was cancelled due to the risk of the Germans noticing that the Canadian troops had withdrawn in readiness for it.

Instead, the 10th Battalion cleared the communication trench of enemy for 100 yards, under concentrated fire from the enemy, and this is when Gilbert met his death, after only three weeks in France, hit be German shellfire while attempting to repair the communication lines.

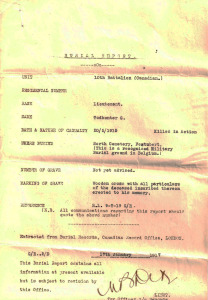

The Regimental War Diary (below) outlines the difficulties encountered on that day, the casualties and the further dangers which caused the C.O. to cancel the planned attack set for that evening. In the margin it also records that Gilbert was killed and another officer wounded by shellfire.

Following further re-evaluation and re-planning, Currie & Guthrie led the Canadians eventually to take K5 and other objectives on 24th May after fierce and prolonged fighting. The Canadian cavalry took over from the 10th Battalion, and the action moved towards other villages in the area including Givenchy and La Bassee.

The battle of Festubert itself was concluded on the 25th May. The allies had suffered 16,000 casualties, 2,204 of which were Canadians, including 97 officers (including Gilbert). Little advantage had been gained, because although the artillery bombardment was more successful than at Aubers, little surprise was achieved and German artillery and movement of reserves was not suppressed as it should have been. Intelligence was still poor, and the trench layout still hindered free movement of reserves and casualties. The allied artillery was in poor condition and insufficiently supplied with ammunition.

The village of Festubert itself of course suffered severe damage after the battle (left). The photo (right) of the nearby landscape was taken in 1919, showing how it would take many years for the devastation caused by WW1 to be rectified. (These pictures can be compared with the photos above, taken in the immediate aftermath of the war).

The village of Festubert itself of course suffered severe damage after the battle (left). The photo (right) of the nearby landscape was taken in 1919, showing how it would take many years for the devastation caused by WW1 to be rectified. (These pictures can be compared with the photos above, taken in the immediate aftermath of the war).

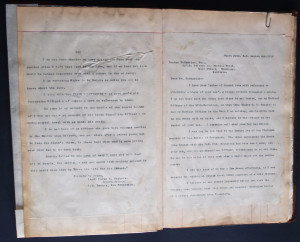

The Aftermath of Gilbert’s Death: After his death Gilbert’s Commanding Officer, Lieut. Col. Percy A. Guthrie, wrote to George on 4th August 1916 c/o the CPR Telegraphy office in Winnipeg. This was to inform him of the circumstances of Gilbert’s death, reproduced from Harriet’s scrapbook, as follows:

“It was during the fiercest moments of the Battle of Festubert. The wires connecting the front line trench with the O.C. 8th Battalion had been swept away and your son, who was my Signalling Officer, volunteered to repair them. He was in the midst of this work when a shell wiped out the entire party. I believe he was almost instantly killed and that the remains were brought back that night and received a Christian burial in a little churchyard near Festubert. I do not know of any officer who gave more valuable service than Gilbert, nor was there ever a braver young man to face the death’s storm, in these days when shells were piling over with few to be sent back”. The actions of Gilbert’s battalion were described in an article written by Gilbert’s CO, Lt.-Col. Guthrie, and others, for the Winnipeg Telegraph. In this, (see col.2 under sub-heading “Germans had the Range”),

Gilbert’s death is mentioned as follows: “During the night, accompanied by Lieut. Nicol, I made another reconnaissance, as there was some dispute between ourselves and the artillery as to the location of certain points, and we prepared a map with compass bearings, which was afterwards declared correct. Nicol, by the way, took the place of Lieut. Todhunter, who for some time had acted as signal officer, and who, unfortunately, was killed by a shell the day before. Although but a boy, he was wonderfully proficient in this work, and his loss was deeply felt by us all. He was from Winnipeg and had a wife and two kiddies, which he left behind him when he answered the call”.

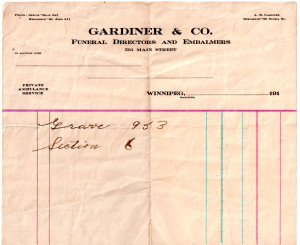

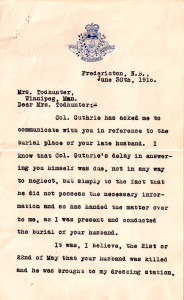

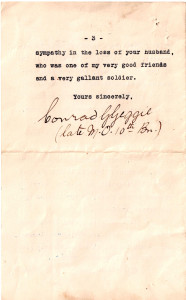

Gilbert’s story was not yet quite at an end. As many as possible of his belongings were retrieved from France and returned to Harriet, who had of course been notified of his death at the earliest opportunity. His remains were subsequently moved, more than once, before arriving at their final resting place. Lt. Col. Guthrie’s Medical Officer wrote to Harriet in England on June 30th 1916:

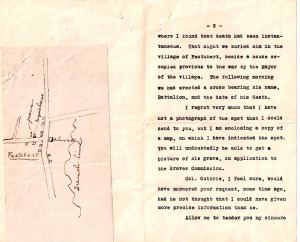

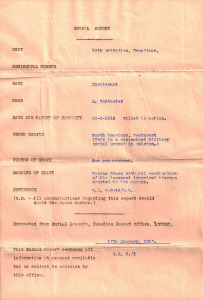

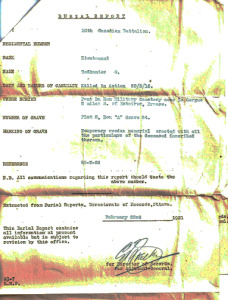

This letter gave details of his initial burial place with a wooden cross in Festubert, together with a sketch map of its location. On March 1st 1917 the Adjutant-General of the Canadian Militia sent Harriet (still in England) the formal burial report:

There was then a second letter with burial reports:

There was then a second letter with burial reports:

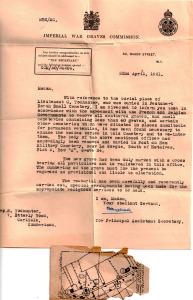

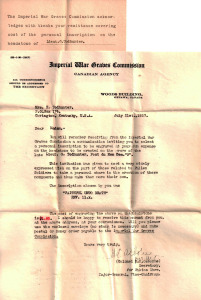

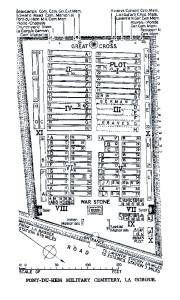

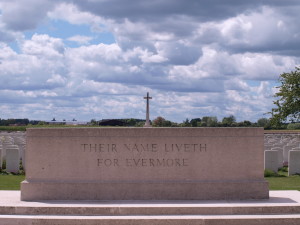

This was sent on 23rd February 1921. On 22nd April 1921, the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWC) wrote to Harriet (by this time in the USA), informing her of the location of Gilbert’s final resting place, the Military Cemetery at Pont-du-Hem, France (below).

As stated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, “There are now over 1,500 1914-18 war casualties commemorated in this site. Of these, over half are unidentified and special memorials are erected to nine soldiers from the United Kingdom believed to be buried among them. Other special memorials record the names of 44 soldiers from the United Kingdom, two from Canada, two from Australia and one of the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry, buried in this or other cemeteries, whose graves were destroyed by shell fire, and of five Indian soldiers whose bodies were cremated. There are 107 German burials and 1 American“.

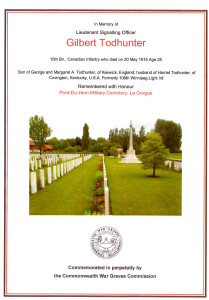

There are also two commemorative certificates regarding his burial place, one above) from the Canadian Government, shown here with compliments slip, and one (below) from the Commonwealth (formerly (Imperial) War Graves Commision, with accompanying plan of Pont du Hem cemetary.

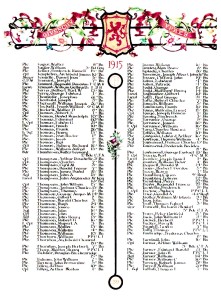

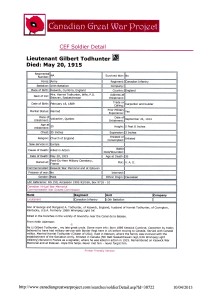

The Canadian Veterans’ Roll of Honour for 1915 lists Gilbert among all the other Canadians fallen that year, and the Canadian Great War project also includes a Soldier Detail entry for Gilbert (NB the footnote to this entry was added by Keith Adamson, Great-Nephew to Gilbert. Keith still lives near Keswick, Gilbert’s home town in England).

The Keswick at War, Canada at War, Saskatchewan and Estevan Virtual War Memorials also all carry entries for Gilbert, as did the Cumberland News, and the Keswick Reminder, the local paper for Keswick carried this lengthy obituary:

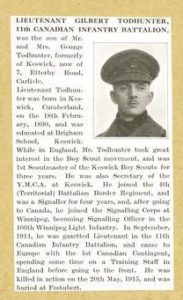

Other summaries of Gilbert’s life are published in astreetnearyou.org, and the Imperial War Museum’s (IWM) “Lives of the First World War”. “Biographies of Fallen British Soldiers”, also accessible via the IWM, contains the following:

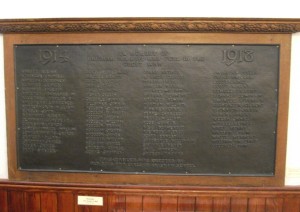

Gilbert’s name appears on both the Keswick War Memorial and the Brigham School memorial plaque for WW1 (now in Keswick Museum):

Also, according to the entry for St Brides Churchyard, Kirkbride, on the War Memorials Online website, “on a gravestone in the Churchyard is a commemoration of another village victim: Gilbert Todhunter of 106 Winnipeg Light Infantry, killed in action 24th (sic) May 1915″. This transpires to be the headstone of Gilbert’s mother Margaret, who ended her days in Wigton nearby. Gilbert’s father George and Sister Agnes are also commemorated on this stone, although they are not buried there either. (Kirkbride is a village between Carlisle, Silloth & Wigton in Cumbria. It is not known at present exactly what was the family’s connection with this village; it is thought that one or more members of the Todhunter or Graham families, some of whom would have lived nearby, may have arranged this – maybe his Uncle Jack, or his Aunt Martha, who shared that little house in Keswick with Gilbert’s family?).

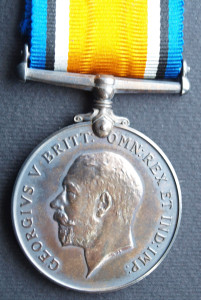

Posthumously, Gilbert was awarded…

–

–

– the 1914-15 Star:

– the WW1 Victory Medal:

These three together being known as “Pip, Squeak & Wilfred“.

He also obtained the WW1 Peace Medal (only the ribbon remains):

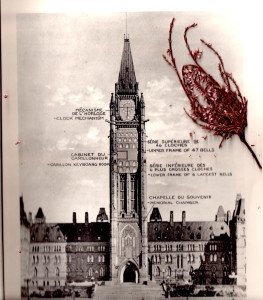

Finally there were two national memorial services held after the war for those fallen in WW1. One took place in London (date unknown), see booklet below.  The other service was held at the Canadian Houses of Parliament in Ottawa, on 3rd August 1927. Two booklets were issued for this. In the first, Harriet had enclosed a sprig of heather (below).

The other service was held at the Canadian Houses of Parliament in Ottawa, on 3rd August 1927. Two booklets were issued for this. In the first, Harriet had enclosed a sprig of heather (below).

The second booklet was focused particularly upon a dedication at the altar.

Meanwhile, Harriet had to carry on with her life, now as a widow with a young child. She had received many notices and letters of condolence, both formal and informal, and other communications concerning Gilbert’s death & burial, his awards and other matters related to his death, before eventually starting out on a new life, a new role and in a new country. This life is outlined under Harriet’s Story.

_________

The Centenary of the Outbreak of WW1, 2014

The UK declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. To commemorate the Centenary of this event, ceremonies were held across the UK and Europe on and around 4th August 2014.

One of these was at Folkestone, where the hill down which Gilbert and his comrades marched in April 1915 was renamed the “Road of Remembrance” (right).

One of these was at Folkestone, where the hill down which Gilbert and his comrades marched in April 1915 was renamed the “Road of Remembrance” (right).

At the top of this hill was erected a Memorial Arch (left) to the 10 million troops who were estimated to have embarked from Folkestone during WW1.This was opened by H.R.H. Prince Harry on 4th August.

At the top of this hill was erected a Memorial Arch (left) to the 10 million troops who were estimated to have embarked from Folkestone during WW1.This was opened by H.R.H. Prince Harry on 4th August.

Gilbert has been specifically recognised in several of the other events, as well as on some of the special websites have been created to the honour of those fallen:

The Tower of London Poppies: between August & November 2014, some 888,246 ceramic poppies were made and installed in the moat of the Tower of London ( see http://poppies.hrp.org.uk/). Gilbert’s great-great-nephew, Alastair Gordon, captured these photographs (right), where the Weeping Window is visible:

The Tower of London Poppies: between August & November 2014, some 888,246 ceramic poppies were made and installed in the moat of the Tower of London ( see http://poppies.hrp.org.uk/). Gilbert’s great-great-nephew, Alastair Gordon, captured these photographs (right), where the Weeping Window is visible:

Each of these symbolises a member of the UK & Commonwealth armed forces who died in the war.  One of these, shown here (left), had been dedicated to Gilbert, and after Remembrance Day on November 11th it was returned to us to remember him by.

One of these, shown here (left), had been dedicated to Gilbert, and after Remembrance Day on November 11th it was returned to us to remember him by.

(The website https://www.wherearethepoppiesnow.org.uk shows where in the world the owners of all the other poppies are to be found).

The Birmingham Ice Sculptures: This event consisted of the creation of 5,000 figures sculpted in ice for individuals to dedicate to a relative lost in the war and place with the others in Chamberlain Square. The idea is that all these figures will completely melt away, but still leaving the memories for those who follow. Alastair also dedicated one of these to Gilbert, placed it in the square and photographed them as shown here.

The Birmingham Ice Sculptures: This event consisted of the creation of 5,000 figures sculpted in ice for individuals to dedicate to a relative lost in the war and place with the others in Chamberlain Square. The idea is that all these figures will completely melt away, but still leaving the memories for those who follow. Alastair also dedicated one of these to Gilbert, placed it in the square and photographed them as shown here.

British Legion Remembrance Garden, Westminster:  The British Legion have a Remembrance Garden at Westminster in which small wooden crosses adorned with poppies, each dedicated to a particular member of the UK & Commonwealth armed forces who fell in service. In 2014, one of these (right) has been dedicated to Gilbert.

The British Legion have a Remembrance Garden at Westminster in which small wooden crosses adorned with poppies, each dedicated to a particular member of the UK & Commonwealth armed forces who fell in service. In 2014, one of these (right) has been dedicated to Gilbert.

British Legion “Everyman Remembered” website: The British Legion has also created a website enabling descendants to enter basic details about their ancestors fallen in the Great War …

(see http://www.everymanremembered.org/profiles/soldier/597312/).

Imperial War Museum “Lives of the First World War” website: The IWM has created a website to enable descendants of members of WW1 forces to provide what information they can to record as much as possible about them and their lives for current & future generations. A short entry has been created for Gilbert; see https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org (enter “Gilbert Todhunter” in Search box).

——–

The Centenary of Gilbert’s Death, 20th May 2015

In May 2015, Gilbert’s great-nephew Ian Gordon, together with his wife Jenny and elder son Alastair, travelled to Folkestone, Festubert, Pont du Hem, Bailleul and Ypres to visit some of the key places where Gilbert had been, and to take some of the photos which have been included in this site.

We visited Gilbert’s grave at Pont du Hem on the 20th May, exactly 100 years after his death. We found the cemetery quiet, peaceful and immaculately maintained, as are all Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemeteries worldwide, with manicured lawns and plantings of shrubs and flowers among the headstones.

Gilbert’s grave was easy to find from the CWGC’s meticulous records, and we left a little wooden cross at his headstone:

Gilbert’s final resting place

(The inscription is a biblical quotation, most likely chosen by Harriet: “Faithful unto death“).

We Will Remember Him.

That same evening we attended the daily Last Post ceremony at the Menin Gate in Ypres.

We also visited the excellent, revealing and thought-provoking “In Flanders Fields” Museum, in the old Ypres Cloth Hall (below). The website for this museum includes two videos, the latter of which includes a clip of the Last Post ceremony.

_________

The Centenary of the End of WW1, 2018

Du ring 2018, a number of initiatives have been taken in the UK to commemorate the end of the war. One of these is to display the Weeping Window assembly of ceramic poppies from the Tower of London in various locations around the country, including Stoke on Trent where the poppies were made. The Weeping Window is shown here against the historic bottle kiln at Middleport Pottery, Stoke, before being transferred to their final location at the Imperial War Museum, London.

ring 2018, a number of initiatives have been taken in the UK to commemorate the end of the war. One of these is to display the Weeping Window assembly of ceramic poppies from the Tower of London in various locations around the country, including Stoke on Trent where the poppies were made. The Weeping Window is shown here against the historic bottle kiln at Middleport Pottery, Stoke, before being transferred to their final location at the Imperial War Museum, London.

Elsewhere across the UK, cities, towns and villages  commemorate armistice annually in their own ways. For 2018, many communities have built displays of home-made poppies; in Gilbert’s home town of Keswick, our war dead were commemorated in 2018 by this display of hand-made poppies outside St John’s church (right):

commemorate armistice annually in their own ways. For 2018, many communities have built displays of home-made poppies; in Gilbert’s home town of Keswick, our war dead were commemorated in 2018 by this display of hand-made poppies outside St John’s church (right):

On 2nd November 2018 the local paper in Keswick, the Keswick Reminder, carried an article about Gilbert which summarised effectively the contents of this site. This article is reproduced here:

During the week before armistice remembrance in 2018, a ceremony was held each evening – “BEYOND THE DEEPENING SHADOWS” – at the Tower of London moat (where the ceramic poppies had marked the onset of war in 2015), 10,000 torches were lit progressively by Yeoman Warders and volunteers forming a creeping wall of fire as a key element of the formal commemorations of the end of the war, in memory of all those lives lost for us, Gilbert’s among them.

On 10th November 2018, the night before Armistice Day itself, Ian & Alastair Gordon attended this moving event, which is picture d here:

d here:

Another initiative is for individuals, families and schools to commemorate in their own way their gratitude for the sacrifices made by all those who were wounded or killed in WW1 – the “NATION’S THANK YOU” campaign.

Part of this was to join the annual Remembrance Day marches past the Cenotaph in London’s Whitehall on November 11 2018, and Ian & Alastair Gordon were successful in obtaining places there , in the Peoples’ March, where we were honoured to march along in respect of 2nd Lt. Gilbert Todhunter, late of the Canadian Army.

Following the march we visited the Field of Remembrance at Westminster Abbey, where we had again arranged for a small wooden cross Gilbert to be inserted in the Canadians’ section to commemorate Gilbert:

We Will Remember Them.